Jewish Conquest of Canaan

The Book of Joshua or Book of Jehoshua (Hebrew: ספר יהושע Sefer Yĕhôshúa) is the sixth book in the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its 24 chapters tell of the Israelite invasion of Canaan,[1] their conquest and division of the land under the leadership of Joshua, and of serving God in the land.[2] Joshua forms part of the biblical account of the emergence of Israel, which begins with the exodus of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt, continues with the book of Joshua, and culminates in the Book of Judges with the conquest and settlement of the land.[3]

The book is in two roughly equal parts. The first part depicts the campaigns of the Israelites in central, southern and northern Canaan, as well as the destruction of their enemies. The second part details the division of the conquered land among the twelve tribes. The two parts are framed by set-piece speeches by God and Joshua commanding the conquest and at the end warning of the need for faithful observance of the Law (torah) revealed to Moses.[4]

Almost all scholars agree that the book of Joshua holds little historical value for early Israel and most likely reflects a much later period.[5] Although Rabbinic tradition holds that the book was written by Joshua, it is probable that it was written by multiple editors and authors far removed from the times it depicts.[6] The earliest parts of the book are possibly chapters 2–11, the story of the conquest; these chapters were later incorporated into an early form of Joshua written late in the reign of king Josiah (reigned 640–609 BCE), but the book was not completed until after the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians in 586, and possibly not until after the return from the Babylonian exile in 539.[7]

Contents

Structure

I. Transfer of leadership to Joshua (1:1–18)

- B. Joshua's instructions to the people (1:10–18)

II. Entrance into and conquest of Canaan (2:1–5:15)

- A. Entry into Canaan

- 1.Reconnaissance of Jericho (2:1–24)

- 2. Crossing the River Jordan (3:1–17)

- 3. Establishing a foothold at Gilgal (4:1–5:1)

- 4. Circumcision and Passover (5:2–15)

- B. Victory over Canaan (6:1–12:24)

- 1. Destruction of Jericho (6)

- 2. Failure and success at Ai (7:1–8:29)

- 3. Renewal of the covenant at Mount Ebal (8:30–35)

- 4. Other campaigns in central Canaan (9:1–27)

- 5. Campaigns in southern Canaan (10:1–43)

- 6. Campaigns in northern Canaan (11:1–23)

- 7. Summary list of defeated kings (12:1–24)

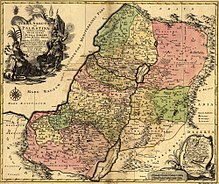

III. Division of the land among the tribes (13:1–22:34)

- A. God's instructions to Joshua (13:1–7)

- B. Tribal allotments (13:8–19:51)

- 1. Eastern tribes (13:8–33)

- 2. Western tribes (14:1–19:51)

- C. Cities of refuge and levitical cities (20:1–21:42)

- D. Summary of conquest (21:43–45)

- E. Dismissal of the eastern tribes (serving YHWH in the land) (22:1–34)

IV. Conclusion (23:1–24:33)

- A. Joshua's farewell address (23:1–16)

- B. Covenant at Shechem (24:1–28)

- C. Deaths of Joshua and Eleazar; burial of Joseph's bones (24:29–33)[4]

Summary

God's commission to Joshua (chapter 1)

Chapter 1 commences "after the death of Moses" (Joshua 1:1) and presents the first of three important moments in Joshua marked with major speeches and reflections by the main characters; here first God, and then Joshua, make speeches about the goal of conquest of the Promised Land; in chapter 12, the narrator looks back on the conquest; and in chapter 23 Joshua gives a speech about what must be done if Israel is to live in peace in the land).[8]

Methodist writer Joseph Benson suggests that God's revelation to Joshua comes "either immediately after [Moses' death], or when the days of mourning for Moses were expired".[9]

God commissions Joshua to take possession of the land and warns him to keep faith with the Covenant. God's speech foreshadows the major themes of the book: the crossing of the Jordan and conquest of the land, its distribution, and the imperative need for obedience to the Law; Joshua's own immediate obedience is seen in his speeches to the Israelite commanders and to the Transjordanian tribes, and the Transjordanians' affirmation of Joshua's leadership echoes Yahweh's assurances of victory.[10]

Entry into the land and conquest (chapters 2–12)

The Israelites cross the Jordan through the miraculous intervention of God and the Ark of the Covenant and are circumcised at Gibeath-Haaraloth (translated as hill of foreskins), renamed Gilgal in memory (Gilgal sounds like Gallothi, I have removed, but is more likely to translate as circle of standing stones). The conquest begins in Canaan with Jericho, followed by Ai (central Canaan), after which Joshua builds an altar to Yahweh at Mount Ebal (northern Canaan) and renews the Covenant. The covenant ceremony has elements of a divine land-grant ceremony, similar to ceremonies known from Mesopotamia.[11]

The narrative then switches to the south. The Gibeonites trick the Israelites into entering into an alliance with them by saying they are not Canaanites; this prevents the Israelites from exterminating them, but they are enslaved instead. An alliance of Amorite kingdoms headed by the Canaanite king of Jerusalem is defeated with Yahweh's miraculous help, and the enemy kings are hanged on trees. (The Deuteronomist author may have used the then-recent 701 BCE campaign of the Assyrian king Sennacherib in Judah as his model; the hanging of the captured kings is in accordance with Assyrian practice of the 8th century).[12]

With the south conquered the narrative moves to the northern campaign. A powerful multi-national (or more accurately, multi-ethnic) coalition headed by the king of Hazor, the most important northern city, is defeated with Yahweh's help and Hazor captured and destroyed. Chapter 11:16–23 summarises the campaign: Joshua has taken the entire land, and the land "had rest from war." Chapter 12 lists the vanquished kings on both sides of the Jordan.

Division of the land (chapters 13–21)

Having described how the Israelites and Joshua have carried out the first of their God's commands, the story now turns to the second, to "put the people in possession of the land." This section is a "covenantal land grant": Yahweh, as king, is issuing each tribe its territory.[13] The "cities of refuge" and Levitical cities are attached to the end, since it is necessary for the tribes to receive their grants before they allocate parts of it to others. The Transjordanian tribes are dismissed, affirming their loyalty to Yahweh.

The book describes how Joshua divided the newly conquered land of Canaan into parcels, and assigned them to the Tribes of Israel by lot.[14] The description serves a theological function to show how the promise of the land was realized in the biblical narrative; its origins are unclear, but the descriptions may reflect geographical relations among the places named.[15] :5

Joshua's farewell (chapters 22–24)

Joshua charges the leaders of the Israelites to remain faithful to Yahweh and the covenant, warning of judgement should Israel leave Yahweh and follow other gods; Joshua meets with all the people and reminds them of Yahweh's great works for them, and of the need to love Yahweh alone. Joshua performs the concluding covenant ceremony, and sends the people to their inheritance.

Composition

The Taking of Jericho (Jean Fouquet, c.1452–1460)

The Book of Joshua is anonymous. TheBabylonian Talmud, written in the 3rd to 5th centuries CE, was the first attempt to attach authors to the holy books: each book, according to the authors of the Talmud, was written by a prophet, and each prophet was an eyewitness of the events described, and Joshua himself wrote "the book that bears his name". This idea was rejected as untenable by John Calvin (1509–1564), and by the time of Thomas Hobbes(1588–1679) it was recognised that the book must have been written much later than the period it depicted.[16]

There is now general agreement that Joshua was composed as part of a larger work, the Deuteronomistic history, stretching fromDeuteronomy to Kings.[17] In 1943 the German biblical scholar Martin Noth suggested that this history was composed by a single author/editor, living in the time of the Exile (6th century BCE).[18] A major modification to Noth's theory was made in 1973 by the American scholar Frank M. Cross, to the effect that two editions of the history could be distinguished, the first and more important from the court of king Josiah in the late 7th century, and the second Noth's 6th century Exilic history.[19] Later scholars have detected more authors or editors than either Noth or Cross allowed for.[20]

Themes and genre

Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still upon Gideon (John Martin)

Historical and archaeological evidence

The prevailing scholarly view is that Joshua is not a factual account of historical events.[21] The apparent setting of Joshua is the 13th century BCE;[21] this was a time of widespread city-destruction, but with a few exceptions (Hazor, Lachish) the destroyed cities are not the ones the Bible associates with Joshua, and the ones it does associate with him show little or no sign of even being occupied at the time.[22]

Given its lack of historicity, Carolyn Pressler, in a recent commentary for the Westminster Bible Companion series, suggests that readers of Joshua should give priority to its theological message ("what passages teach about God") and be aware of what these would have meant to audiences in the 7th and 6th centuries BCE.[23]Richard Nelson explains: The needs of the centralised monarchy favoured a single story of origins combining old traditions of an exodus from Egypt, belief in a national god as "divine warrior," and explanations for ruined cities, social stratification and ethnic groups, and contemporary tribes.[24]

Themes

The overarching theological theme of the Deuteronomistic history is faithfulness (and its opposite, faithlessness) and God's mercy (and its obverse, his anger). In Judges, Samuel, and Kings, Israel becomes faithless and God ultimately shows his anger by sending his people into exile,[25] but in Joshua Israel is obedient, Joshua is faithful, and God fulfills his promise and gives them the land.[26] Yahweh's war campaign in Canaan validates Israel's entitlement to the land[27] and provides a paradigm of how Israel was to live there: twelve tribes, with a designated leader, united by covenant in warfare and in worship of Yahweh alone at single sanctuary, all in obedience to the commands of Moses as found in Deuteronomy.[28]

God and Israel

Joshua takes forward Deuteronomy's theme of Israel as a single people worshiping Yahweh in the land God has given them.[29] Yahweh, as the main character in the book, takes the initiative in conquering the land, and it is Yahweh's power that wins battles (for example, the walls of Jericho fall because Yahweh is fighting for Israel, not because the Israelites show superior fighting ability).[30] The potential disunity of Israel is a constant theme, the greatest threat of disunity coming from the tribes east of the Jordan, and there is even a hint in chapter 22:19 that the land across the Jordan is unclean and the tribes who live there are of secondary status.[31]

Land

Land is the central topic of Joshua.[32] The introduction to Deuteronomy recalled how Yahweh had given the land to the Israelites but then withdrew the gift when Israel showed fear and only Joshua and Caleb had trusted in God.[33] The land is Yahweh's to give or withhold, and the fact that he has promised it to Israel gives Israel an inalienable right to take it. For exilic and post-exilic readers, the land was both the sign of Yahweh's faithfulness and Israel's unfaithfulness, as well as the centre of their ethnic identity. In Deuteronomistic theology, "rest" meant Israel's unthreatened possession of the land, the achievement of which began with the conquests of Joshua.[34]

The enemy

Joshua "carries out a systematic campaign against the civilians of Canaan — men, women and children — that amounts to genocide."[35] In doing this he is carrying outherem as commanded by Yahweh in Deuteronomy 20:17: "You shall not leave alive anything that breathes." The purpose is to drive out and dispossess the Canaanites, with the implication that there are to be no treaties with the enemy, no mercy, and no intermarriage.[10] This purpose is further supported by the implication that Yahweh would send a plague of hornets to wherever Israel's campaign would bring them to next, resulting in the majority of the Canaanite people being displaced rather than caught up in the slaughter when the Israelites arrived. See Exodus 23:28 and Deuteronomy 7:20. "The extermination of the nations glorifies Yahweh as a warrior and promotes Israel's claim to the land," while their continued survival "explores the themes of disobedience and penalty and looks forward to the story told in Judges and Kings."[36] The divine call for massacre at Jericho and elsewhere can be explained in terms of cultural norms (Israel wasn't the only Iron Age state to practice here) and theology (a measure to ensure Israel's purity as well as the fulfillment of God's promise),[10] but Patrick D. Miller in his commentary on Deuteronomy remarks, "there is no real way to make such reports palatable to the hearts and minds of contemporary readers and believers."[37]

Obedience

Obedience vs. disobedience is a constant theme.[38] Obedience ties in the Jordan crossing, the defeat of Jericho and Ai, circumcision and Passover, and the public display and reading of the Law. Disobedience appears in the story of Achan (stoned for violating the herem command), the Gibeonites, and the altar built by the Transjordan tribes. Joshua's two final addresses challenge the Israel of the future (the readers of the story) to obey the most important command of all, to worship Yahweh and no other gods. Joshua thus illustrates the central Deuteronomistic message, that obedience leads to success and disobedience to ruin.[39]

Moses, Joshua and Josiah

The Deuteronomistic history draws parallels in proper leadership between Moses, Joshua and Josiah.[40] God's commission to Joshua in chapter 1 is framed as a royal installation, the people's pledge of loyalty to Joshua as successor Moses recalls royal practices, the covenant-renewal ceremony led by Joshua was the prerogative of the kings of Judah, and God's command to Joshua to meditate on the "book of the law" day and night parallels the description of Josiah in 2 Kings 23:25 as a king uniquely concerned with the study of the law — not to mention their identical territorial goals (Josiah died in 609 BCE while attempting to annex the former Israel to his own kingdom of Judah).[41]

Some of the parallels with Moses can be seen in the following, and not exhaustive, list:[17]

- Joshua sent spies to scout out the land near Jericho (2:1), just as Moses sent spies from the wilderness to scout out the Promised Land (Num. 13; Deut. 1:19–25).

- Joshua led the Israelites out of the wilderness into the Promised Land, crossing the Jordan River as if on dry ground (3:16), just as Moses led the Israelites out of Egypt through the Red Sea, which they crossed as if on dry land (Ex. 14:22).

- After crossing the Jordan River, the Israelites celebrated the Passover (5:10–12) just as they did immediately before the Exodus (Ex. 12).

- Joshua's vision of the "commander of Yahweh's army" (5:13–15) is reminiscent of the divine revelation to Moses in the burning bush (Ex. 3:1–6).

- Joshua successfully intercedes on behalf of the Israelites when Yahweh is angry for their failure to fully observe the "ban" (herem), just as Moses frequently persuaded God not to punish the people (Ex. 32:11–14, Num. 11:2, 14:13–19).

- Joshua and the Israelites were able to defeat the people at Ai because Joshua followed the divine instruction to extend his sword (Josh 8:18), just as the people were able to defeat the Amalekites as long as Moses extended his hand that held "the staff of God" (Ex. 17:8–13).

- Joshua served as the mediator of the renewed covenant between Yahweh and Israel at Shechem (8:30–35; 24), just as Moses was the mediator of Yahweh's covenant with the people at Mount Sinai/Mount Horeb.

- Before his death, Joshua delivered a farewell address to the Israelites (23–24), just as Moses had delivered his farewell address (Deut. 32–33).

See also

References

- Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary | Freedman, D. N., Herion, G. A., Graf, D. F., Pleins, J. D., & Beck, A. B. (Eds.). (1992) | New York: Doubleday. | Book of Joshua

- McConville (2001), p.158

- McNutt, p.150

- Achtemeier and Boraas

- Killebrew, pp.152

- Creach, pp.9–10

- Creach, pp.10–11

- De Pury, p.49

- Benson Commentary on Joshua 1, accessed 3 August 2016

- Younger, p.175

- Younger, p.180

- Na'aman, p.378

- Younger, p.183

- "JOSHUA, BOOK OF - JewishEncyclopedia.com".

- Dorsey, David A. (1991). The Roads and Highways of Ancient Israel. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-3898-3.

- De Pury, pp.26–30

- Younger, p.174

- Klein, p.317

- De Pury, p.63

- Knoppers, p.6

- McConville (2010), p.4

- Miller&Hayes, pp. 71–2.

- Pressler, pp.5–6

- Nelson, p.5

- Laffer, p.337

- Pressler, pp.3–4

- McConville (2001), pp.158–159

- Coogan 2009, p. 162.

- McConville (2001), p.159

- Creach, pp.7–8

- Creach, p.9

- McConville (2010), p.11

- Miller (Patrick), p.33

- Nelson, pp.15–16

- Dever, p.38

- Nelson, pp.18–19

- Miller (Patrick), pp.40–41

- Curtis, p.79

- Nelson, p.20

- Nelson, p.102

- Finkelstein, p.95

Bibliography

Translations of Joshua

Commentaries on Joshua

- Auzou, Georges (1964). Le Don d'une conquête: étude du livre de Josué (in series, Connaissance de la Bible, 4). Éditions de l'Orante.

- Creach, Jerome F.D (2003). Joshua. Westminster John Knox Press.ISBN 9780664237387.

- Curtis, Adrian H.W (1998). Joshua. Sheffield Academic Press.ISBN 9781850757061.

- Harstad, Adolph L. (2002). Joshua (in series, Concordia Commentary). Arch Books. ISBN 978-0-570-06319-3.

- McConville, Gordon; Williams, Stephen (2010). Joshua. Eerdmans.ISBN 9780802827029.

- McConville, Gordon (2001). "Joshua". In John Barton; John Muddiman. Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198755005.

- Miller, Patrick D (1990). Deuteronomy. Cambridge University Press.ISBN 9780664237370.

- Nelson, Richard D (1997). Joshua. Westminster John Knox Press.ISBN 9780664226664.

- Pressler, Carolyn (2002). Joshua, Judges and Ruth. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664255268.

- Younger, K. Lawson Jr (2003). "Joshua". In James D. G. Dunn; John William Rogerson. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans.ISBN 9780802837110.

General

- Achtemeier, Paul J; Boraas, Roger S (1996). The HarperCollins Bible Dictionary. HarperSanFrancisco.

- Bright, John (2000). A History of Israel. Westminster John Knox Press.ISBN 9780664220686.

- Campbell, Anthony F (1994). "Martin Noth and the Deuteronomistic History". In Steven L. McKenzie; Matt Patrick Graham. The history of Israel's traditions: the heritage of Martin Noth. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9780567230355.

- Campbell, Anthony F; O'Brien, Mark (2000). Unfolding the Deuteronomistic history: origins, upgrades, present text. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451413687.

- Coogan, Michael D. (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament. Oxford University Press.

- Day, John (2002). Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9780826468307.

- De Pury, Albert; Romer, Thomas (2000). "Deuteronomistic Historiography (DH): History of Research and Debated Issues". In Albert de Pury; Thomas Romer; Jean-Daniel Macchi. Israël constructs its history: Deuteronomistic historiography in recent research. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9780567224156.

- Dever, William (2003). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802809759.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2001). The Bible Unearthed. Free Press.ISBN 9780743223386.

- Killebrew, Ann E. (2005). Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, and Early Israel, 1300–1100 B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589830974.

- Klein, R.W. (2003). "Samuel, books of". In Bromiley, Geoffrey W. The international standard Bible encyclopedia. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837844.

- Knoppers, Gary (2000). "Introduction". In Gary N. Knoppers; J. Gordon McConville.Reconsidering Israel and Judah: recent studies on the Deuteronomistic history. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060378.

- Laffey, Alice L (2007). "Deuteronomistic history". In Orlando O. Espín; James B. Nickoloff. An introductory dictionary of theology and religious studies. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814658567.

- McNutt, Paula (1999). Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664222659.

- Miller, James Maxwell; Hayes, John Haralson (1986). A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-21262-X.

- Naʾaman, Nadav (2005). Ancient Israel and Its Neighbors: Collected Essays: Volume 2. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061139.

- Van Seters, John (2000). "The Deuteronomist from Joshua to Samuel". In Gary N. Knoppers; J. Gordon McConville. Reconsidering Israel and Judah: Recent Studies on the Deuteronomistic History. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060378.

Tribal allotments of Israel: Books and maps

- Abu-Sitta, Salman H. (2004). Atlas of Palestine, 1948. Palestine Land Society.

- Aharoni, Yohanan (1979). The Land of the Bible; A Historical Geography. The Westminster Press. ISBN 0-664-24266-9.

- Campbell, E., Jr. (1991). Shechem II. ASOR. ISBN 0-89757-062-6.

- Dever, William G. (2003). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0975-8.

- Finkelstein, I. and Z. Lederman (eds.) (1997). Highlands of Many Cultures: The Southern Samaria Survey. Tel Aviv University Institute of Archaeology. ISBN 965-440-007-3.

- Curtis, Adrian (2009). Oxford Bible Atlas, Fourth Edition. Oxford University Press.ISBN 9780199560462.

- Kallai, Zecharia (1986). Historical Geography of the Bible; The Tribal Territories of Israel. The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University. ISBN 965-223-631-4.

- Miller, Robert D., II, (2005). Chieftains Of The Highland Clans: A History Of Israel In The Twelfth And Eleventh Centuries B.C. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0988-X.

- Na'aman, Nadav (1986). Borders and Districts in Biblical Historiography. Simor, Ltd. ISBN 965-242-005-0.

External links

- Original text

- יְהוֹשֻׁעַ Yehoshua–Joshua (Hebrew–English at Mechon-Mamre.org, Jewish Publication Society translation)

- Jewish translations

- Joshua (Judaica Press) translation with Rashi's commentary at chabad.org

- Christian translations

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org

- Joshua at Wikisource (Authorised King James Version)

Joshua public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

Joshua public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

According to the Bible, after the Exodus from Egypt, the Israelites moved into Canaan, the land promised to them by God. The Book of Joshua, describing the early Israelite campaigns, relates how they entered Canaan with two fierce battles (Jericho and Ai) and gained control of the land through their campaigns against the Canaanite kings of north and south.

This picture has been dramatically revised as a result of the archaeological evidence, as Jericho and Ai were not occupied in the Near Eastern Late Bronze Age, and the destruction of other cities as recounted in Joshua cannot be assigned to the Israelites.[1] As a result there is general agreement among scholars that the Book of Joshua holds little historical value.[2] The story of the conquest represents the nationalist propaganda of the 8th century kings of Judah and their claims to the territory of the Kingdom of Israel;[3] incorporated into an early form of Joshua written late in the reign of king Josiah (reigned 640–609 BCE). The book was revised and completed after the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians in 586, and possibly after the return from the Babylonian exile in 538.[4]

Biblical narrative

According to the Biblical narrative, the Israelites successfully attack the Canaanitesat such locations as Jericho and Ai. In the south, Joshua honors the treaty withGibeon and defeats the kings of five cities — Jerusalem, Hebron, Jarmuth, Lachish, and Eglon (ch.10). Soon, a coalition of Canaanites and other northern city-states of Canaan send a force to halt the Israelite invasions of their country. However, an Israelite counterattack catches their enemies by surprise at the Waters of Meromand routs them (ch.11). In chapter 12, Joshua lists 32 cities reportedly conquered by the Israelite army. Afterwards, the Israelites become established in their "Promised Land".

However, scholars have also raised concerns about inconsistencies in the Biblical representation of how the Israelites emerged in Canaan, especially between the books of Joshua and Judges.[5]

Scholarship

In early 20th century academic scholarship, the historicity of the early Israelite campaigns was taken for granted (e.g., Paton). However, by the 1930s Martin Noth issued what Albricht termed "a sweeping criticism of the legitimacy of using biblical data in Joshua as material for history."[6] Noth was a student of Alt, who emphasizedform criticism and the importance of etiology.[7] Alt and Noth posited a peaceful movement of the Israelites into various areas of Canaan, contra the Biblical account.[8]

Albricht himself questioned the "tenacity" of etiologies, which were key to Noth's analysis of the campaigns in Joshua. Archaeological evidence in the 1930s showed that the city of Ai, an early battled in the putative Joshua account, had existed and been destroyed, but in 22nd century BCE.[9] Kathleen Kenyon showed that Jericho was from the Middle not the Late Bronze Age[10] Hence, it was argued that the early Israelite campaign could not be historically corroborated, but rather explained as an etiology of the location and a representation of the Israelite settlement.

In 1955, Wright discusses the correlation of archaeological data to the early Israelite campaigns, which he divides into three phases per the Book of Joshua. He points to two sets of archaeological findings that "seem to suggest that the biblical account is in general correct regarding the nature of the late thirteenth and twelfth-eleventh centuries in the country" (i.e., "a period of tremendous violence").[11] He gives particular weight to what were recent digs at Hazor by Yigael Yadin.[12]

As an alternative to both the military conquest and uncontested infiltration hypotheses, Mendenhall and Gottwald suggested that the Israelites emerged through a kind of peasant revolt against their Canaanite lords. However, as explained by Rendsburg (p.510f.), archaeological findings (presented by Israel Finkelstein in 1986) undermined this idea because the Israelites first settled areas not held by Canaanites, whose cities were sustained alongside Israelite areas.

In later years of the 20th century, academic analysis tended to be increasingly skeptical of the historicity of the early Israelite military campaigns as described in Joshua. To be sure, scholarship remained somewhat divided with some more deferential to the Biblical account. For example, Kennedy argues that "a vast amount of archaeological evidence indicates that the sites of Jericho, Hazor, Shechem, and Dan were occupied, destroyed, and resettled at the specific times and in the manner consistent with the records from the books of Joshua and Judges."

On the other hand, the work of Dever and Van Seters, among others, pulls back considerably from the presuppositions of early scholars.

Whether through pastoral migration or military conquest, the Israelite settlement cannot easily be pegged to a specific time period. Scholars have argued the 14th, 13th, and 12th centuries BCE.[13]

Moral and political interpretations

With the Zionist struggle for a Jewish state, the early Israelite campaigns have undergone renewed attention and interpretation. The early Zionists, according toRachel Havrelock, "read the book of Joshua as explaining their times and justifying their wars. From this perspective, God fought on behalf of manifest Israel.... Joshua’s vocabulary informed the lexicon of Jewish nationalism."[14]

Later, in 1958, David Ben-Gurion "saw the biblical war narrative as constituting an ideal basis for a unifying myth of national identity." This was a unity that was framed against a common enemy, Arabs beyond Israel's borders.[15] Ben-Gurion met with politicians and scholars, such as Bible scholar Shemaryahu Talmon, to discuss the conquests in Joshua. He later published a book of the meeting transcripts. In a lecture at Ben-Gurion's home, archaeologist Yigael Yadin argued for the historicity of the Israelite military campaign and remarked on how much easier it was for military experts to appreciate the plausibility of the Joshua narrative. Yadin specifically pointed to the conquests of Hazor, Bethel, and Lachish. Conversely, archaeologist Yohanan Aharoni argued against the historicity of the early Israelite campaigns, instead favoring a migration model.[16]

Havrelock herself argues that the myth of conquest, although shaped by ardent nationalists with a military agenda, could be re-interpreted for the purposes of a decentralized post-nationalism.[17]

By the same token, the Biblical narrative of conquest has been used as an apparatus of critique against Zionism. For example, Michael Prior criticizes the use of the campaign in Joshua to favor "colonial enterprises" (in general, not only Zionism) and have been interpreted as validating ethnic cleansing. He asserts that the Bible was used to make the treatment of Palestinians more palatable morally.[18]A related moral condemnation can be seen in "The political sacralization of imperial genocide: contextualizing Timothy Dwight's The Conquest of Canaan" by Bill Templer.[19] This kind of critique is not new; Jonathan Boyarin notes how Frederick W. Turner blamed Israel's monotheism for the very idea of genocide, which Boyarin found "simplistic" yet with precedents.[20]

References

- Rogerson & Lieu 2006, p. 63.

- Killebrew, p. 152.

- Coote 2000, p. 275.

- Creach 2003, p. 10–11.

- See Kennedy's discussion and attempted resolution, p.3., and Japhet p.206ff.

- Albricht, April 1939, p.12

- Abricht, ibid. Kennedy (p.2) cites later scholarship behind this model, e.g., Noort 1998: 127-28.

- Rendburg, p.510

- Albricht, p.16

- see Kennedy, p.11

- Wright, p.107

- Wright, p.107

- For a review, see Kennedy, among others.

- Havrelock, Rachel (2013). "The Joshua Generation: Conquest and the Promised Land". Critical research on religion 1 (3): 309. doi:10.1177/2050303213506473.

- Havrelock, p.309

- Havrelock, p.310f.

- Havrelock, p.310

- Prior, Michael (2002). "Ethnic Cleansing and the Bible: A Moral Critique". Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies 1 (1): 37–59.

- Templer, Bill (1 December 2006). "The political sacralization of imperial genocide: contextualizing Timothy Dwight's The Conquest of Canaan". Postcolonial Studies: Culture, Politics, Economy 9 (4): 358–391.doi:10.1080/13688790600993230.

- Boyarin p.525

Bibliography

- Coote, Robert B. (2000). "Conquest: Biblical narrative". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans.

- Creach, Jerome F.D (2003). Joshua. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Dever, William G. (2006). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?. Eerdmans.

- Jacobs, Paul F. (2000). "Jericho". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C.Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans.

- Killebrew, Ann E. (2005). Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, and Early Israel, 1300–1100 B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature.

- Laffey, Alice L. (2007). "Deuteronomistic history". In Espín, Orlando O.; Nickoloff, James B. An introductory dictionary of theology and religious studies. Liturgical Press.

- Moore, Megan Bishop; Kelle, Brad E. (2011). Biblical History and Israel's Past. Eerdmans.

- Bruins, Hendrik J.; Van Der Plicht, Johannes (1995). "Tell Es-Sultan (Jericho): Radiocarbon Results..." (PDF). Radiocarbon (Proceedings of the 15th International 14C Conference). 37, no.2: 213–220.

- Albright, William F. "The Israelite conquest of Canaan in the light of archaeology." Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (1939): 11-23.

- Briggs, Peter. "Testing the Factuality of the Conquest of Ai Narrative in the Book of Joshua." Beyond the Jordan: Studies in Honor of W. Harold Mare (2005): 157-96.

- Dever, William G. Who were the early Israelites, and where did they come from?. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2003.

- Hess, Richard S. "The Jericho and Ai of the Book of Joshua." Critical Issues in Early Israelite History (2008): 29-30.

- Kennedy, Titus Michael. "The Israelite conquest: history or myth?: an achaeological evaluation of the Israelite conquest during the periods of Joshua and the Judges." (2011). http://uir.unisa.ac.za/handle/10500/5727

- Kenyon, Kathleen. “Some Notes on the History of Jericho in the Second Millennium. B.C.,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 83 (1951)

- Mendenhall, George E. 1962. “The Hebrew Conquest of Palestine,” The Biblical Archaeologist, 25:3 (1962): 66-87

- Noort, Ed. 1998. "4QJOSH and the History of Tradition in the Book of Joshua," Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages, 24:2 (1998): 127-44

- Rendsburg, Gary A. "The Date of the Exodus and the Conquest/Settlement: The Case for the 1100s." Vetus Testamentum (1992): 510-527.

- Van Seters, John. "Joshua's campaign of Canaan and near eastern historiography." Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 4.2 (1990): 1-12.

- Wenham, Gordon J. "The Deuteronomic Theology of the Book of Joshua." Journal of Biblical Literature (1971): 140-148.

- Wright, G. Ernest. "Archaeological News and Views: Hazor and the Conquest of Canaan." The Biblical Archaeologist 18.4 (1955): 106-108.

- Zevit, Ziony. "Archaeological and Literary Stratigraphy in Joshua 7-8." Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (1983): 23-35.

Other academic writings

- Bayles Paton, Lewis. Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912. Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Apr., 1913), pp. 1–53

- Billauer, Barbara P. "Joshua's Battle of Jericho: Scientific Statecraft in Warfare-Lessons in Military Innovation and Scientific Tactical Initiative."Available at SSRN 2219488 (2013).

- Boyarin, Jonathan. "Reading exodus into history." New Literary History (1992): 523-554.

- den Braber, Marieke, and Jan-Wim Wesselius. "The Unity of Joshua 1-8, its Relation to the Story of King Keret, and the Literary Background to the Exodus and Conquest Stories." Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 22.2 (2008): 253-274.

- Havrelock, Rachel. "The Joshua Generation: Conquest and the Promised Land." Critical Research on Religion 1, no. 3 (2013): 308-326.

- Hawk, L. Daniel. "The Truth about Conquest: Joshua as History, Narrative, and Scripture." Interpretation 66.2 (2012): 129-140.

- Gyémánt, Ladislau. "Historiographic Views on the Settlement of the Jewish Tribes in Canaan." Sacra Scripta 1 (2003): 26-30.

- Japhet, Sara. "Conquest and Settlement in Chronicles." Journal of Biblical Literature (1979): 205-218.

- Pienaar, Daan. "Some observations on conquest reports in the Book of Joshua." Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages 30.1 (2004): 151-164.

- Prior, Michael. "Ethnic Cleansing and the Bible: A Moral Critique." Holy Land Studies 1.1 (2002): 37-59.

- Thompson, Leonard L. "The Jordan Crossing: Ṣidqot Yahweh and World Building." Journal of Biblical Literature (1981): 343-358.

- Wazana, Nili. "Everything Was Fulfilled” versus “The Land That Yet Remains."The Gift of the Land and the Fate of the Canaanites in Jewish Thought (2014): 13.

- Wood, W. Carleton. "The Religion of Canaan: From the Earliest Times to the Hebrew Conquest (Concluded)." Journal of Biblical literature (1916): 163-279.

Battle of Jericho

According to the Book of Joshua, the Battle of Jericho was the first battle of the Israelites in their conquest of Canaan. According to Joshua 6:1-27, the walls of Jericho fell after Joshua's Israelite army marched around the city blowing their trumpets. Excavations at Tell es-Sultan, the biblical Jericho, have failed to produce data to substantiate the biblical story,[2] and scholars are virtually unanimous that the Book of Joshua holds little of historical value.[3]

Joshua 6:1-27

The story of Jericho is told in Joshua 6:1-27.

The first five books of the Hebrew Bible tell how Noah cursed Canaan to become a slave, and how God gave the land of the Canaanites to Abraham and his descendants. The children of Israel (descendants of Abraham) themselves became slaves in Egypt, but through Moses God brought them out of Egypt and to the borders of the promised land of Canaan. There Moses instructed them to seize the land by conquest, and placed them under the command of Joshua.

Joshua sent spies to Jericho, the first city of Canaan to be taken, and discovered that the land was in fear of Israel and their God. The Israelites marched around the walls once every day for seven days with the priests and the Ark of the Covenant. On the seventh day they marched seven times around the walls, then the priests blew their ram's horns, the Israelites raised a great shout, and the walls of the city fell. Following God's law of herem the Israelites took no slaves or plunder but slaughtered every man, woman and child in Jericho, sparing only Rahab, a Canaanite prostitute who had sheltered the spies, and her family.

Origins and historicity

In 1868, Charles Warren identified Tell es-Sultan as the site of Jericho. In 1930–36,John Garstang conducted excavations there and discovered the remains of anetwork of collapsed walls which he dated to about 1400 BCE, the accepted biblical date of the conquest. Kathleen Kenyon re-excavated the site over 1952–1958 and demonstrated that the destruction occurred c.1500 BCE during a well-attested Egyptian campaign of that period, and that Jericho had been deserted throughout the mid-late 13th century.[4] Kenyon's work was corroborated in 1995 by radiocarbon tests which dated the destruction level to the late 17th or 16th centuries.[5] A small unwalled settlement was rebuilt in the 15th century, but the tell was unoccupied from the late 15th century until the 10th/9th centuries.[2] In the face of the archaeological evidence, the biblical story of the fall of Jericho "cannot have been founded on genuine historical sources".[6]

Almost all scholars agree that the book of Joshua holds little of historical value.[3] It was written by authors far removed from the times it depicts,[7] and was intended to illustrate a theological scheme in which Israel and her leaders are judged by their obedience to the teachings and laws (the covenant) set down in the book ofDeuteronomy, rather than as history in the modern sense.[8] The story of Jericho, and the conquest generally, probably represents the nationalist propaganda of the kings of Judah and their claims to the territory of the Kingdom of Israel after 722 BCE;[9]these chapters were later incorporated into an early form of Joshua written late in the reign of king Josiah (reigned 640–609 BCE), and the book was revised and completed after the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians in 586, and possibly after the return from the Babylonian exile in 538.[10] The combination of archaeological evidence and analysis of the composition history and theological purposes of the Book of Joshua lies behind the judgement of archaeologist William G. Dever that the battle of Jericho "seems invented out of whole cloth."[6]

See also

- Ai (Bible)

- Biblical archaeology

- Bryant Wood

- Early Israelite campaigns

- "Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho", African-American spiritual about the battle

References

- Joshua 4:13

- Jacobs 2000, p. 691.

- Killebrew 2005, p. 152.

- Dever 2006, p. 45-46.

- Bruins & Van Der Plicht 1995, p. 213.

- Dever 2006, p. 47.

- Creach 2003, p. 9–10.

- Laffey 2007, p. 337.

- Coote 2000, p. 275.

- Creach 2003, p. 10–11.

Bibliography

- Coote, Robert B. (2000). "Conquest: Biblical narrative". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans.

- Creach, Jerome F.D (2003). Joshua. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Dever, William G. (2006). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?. Eerdmans.

- Jacobs, Paul F. (2000). "Jericho". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C.Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans.

- Killebrew, Ann E. (2005). Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, and Early Israel, 1300–1100 B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature.

- Laffey, Alice L. (2007). "Deuteronomistic history". In Espín, Orlando O.; Nickoloff, James B. An introductory dictionary of theology and religious studies. Liturgical Press.

- Moore, Megan Bishop; Kelle, Brad E. (2011). Biblical History and Israel's Past. Eerdmans.

- Bruins, Hendrik J.; Van Der Plicht, Johannes (1995). "Tell Es-Sultan (Jericho): Radiocarbon Results..." (PDF). Radiocarbon. Proceedings of the 15th International 14C Conference. 37 (2): 213–220.

External links

Media related to The Battle of Jericho at Wikimedia Commo

Media related to The Battle of Jericho at Wikimedia Commo

No comments:

Post a Comment